Margaret Sullivan's Journalism Commandments

The first woman Public Editor at the New York Times and retiring Washington Post media columnist on her four-decade wild ride in journalism, detailed in her new book ‘Newsroom Confidential’

Fifty-five years later, the iconic moment from the 1967 film "The Graduate" is still seared in my brain. The Dustin Hoffman character, 21-year-old Benjamin Braddock, is taken aside at his college graduation party by one of his parent's friends who's determined to share career advice: "I have just one word for you ...One word … Are you listening? … Plastics."

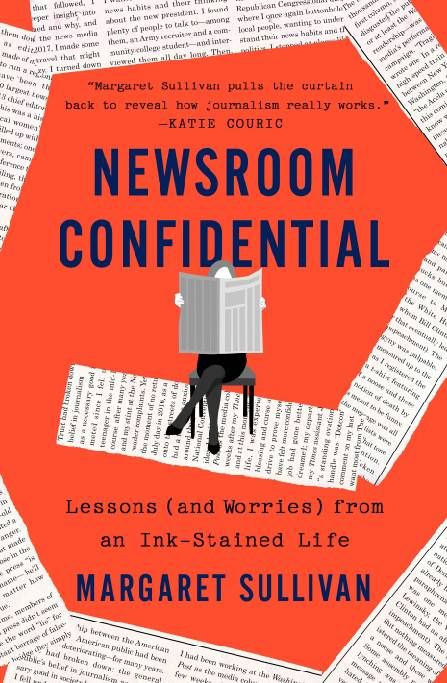

That scene sprung to mind while reading Margaret Sullivan's new book "Newsroom Confidential: Lessons (and Worries) from an Ink-Stained Life," part memoir and part press critique. As a high school student, Sullivan was asked by her eldest brother David, home from college, what she would do for her career. She told him what she might be good at: "Reading. Words. Knowing what's going on. Communicating." And her brother instantly offered a single word of advice: "Journalism."

But unlike "The Graduate's" fictional Braddock, who seemed unexcited with the prospect of a life in plastics, Sullivan was instantly seduced into an ink-stained life by what she calls "the thrills of creativity under deadline." Whether as the editor of her all-girls high school newspaper in Buffalo, New York, where she wrote the editorial reluctantly agreeing with President Gerald Ford's decision to pardon Richard Nixon or while writing and editing at both the traditional and alternative student newspapers at Georgetown University, the newsroom seemed to suit her from the start.

"We are in a time in which journalism has become very fraught."

An internship at the Niagara (New York) Gazette might have meant a summer writing concert reviews and features until one of the biggest stories in the country literally bubbled up nearby. The environmental disaster in the Love Canal neighborhood was an all-hands-on-deck moment. And Sullivan was pressed into service, producing some front-page stories that impressed her editor. She was offered a full-time reporting job on the spot but declined so she could finish her final year at Georgetown.

Later, at the Buffalo News, Sullivan would rise from summer intern to become the first woman editor in chief. Sullivan then headed for the New York Times as the first woman Public Editor and sharpened her press criticism during the Trump and Biden presidencies as media columnist for the Washington Post.

Beginning next year, Sullivan will be a visiting professor at Duke University, where she had previously taught media ethics, teaching a course that she did not name, but loves its provocative title: "News as a Moral Battleground."

Next Avenue spoke with Sullivan from her home in New York City.

Next Avenue: When I wrote my first bylined story in the hometown paper nearly 50 years ago during the summer of the Watergate hearings, I didn't anticipate my chosen profession would become a 'moral battleground.' How did that happen?

Margaret Sullivan: We are in a time in which journalism has become very fraught. Journalists are no longer handing down something from on high. There's much more back and forth between the news consumers or, as I like to idealistically call them, American citizens. Journalism has become part of a very polarized, divisive political discussion that's so troubling both in the United States and actually, around the world. It didn't begin with Trump's ascendancy, but Trump had a lot to do with exacerbating it.

Was it inevitable that people would gravitate to those cable channels or newspapers that would reinforce their worldview?

I suppose it's part of human psychology that we like to have our beliefs reinforced, but it's a relatively new phenomenon that there's the media to do it. And maybe that began in earnest with the coming of the cable networks, which now are largely a place to come to get your outrage on. Interestingly, CNN is seemingly trying to position itself in the middle, but I'm not sure there is a middle. But yes, I think given the technology and the politics of our time, it was inevitable.

As a kid, the first big shared news event I recall was when Water Cronkite took off his glasses and informed the country that President Kennedy died from an assassin's bullet. There may have been conspiracy theories about the grassy knoll, but few doubted what Cronkite announced. Today it seems the truth is constantly under assault. Why are there fewer news stories where everyone can agree, at least, on what happened?

"It's no longer the case that the paper deliverer goes up and down the street and everybody gets the same thing."

There were later moments in which we experienced something huge and did not question it ... 9/11 …. some of the first of the mass school shootings like Columbine, then later, Sandy Hook. I think the whole country experienced those similarly. Where we have really split off is in political news and I would include in that legislation about guns and what's happened in the Supreme Court over abortion rights. Those are the subjects that we don't seem to have a common ground of reality about.

And what's the danger if we keep going on this trajectory?

I always think about something that Rep. Jamie Raskin (D- Maryland) said, quoting his father, Marcus Raskin, who could be described as a progressive political activist. Democracy needs a common ground to stand on, he said. And that ground is the truth. I think it's profound. If we don't have that common basis of reality, we really can't function as a self-governing people.

We seem to have evolved into a country divided into two distinct camps, which means journalists are either preaching to the choir or preaching to people who don't want to be preached to.

Absolutely. It's a huge problem. I think you have described THE problem of journalism today, and I wish I knew how to overcome it. One of the things that has created this is that local journalism has declined so much that we don't share the same kind of news source that our neighbors do. It's no longer the case that the paper deliverer goes up and down the street and everybody gets the same thing. Not that that was always serving every population very well … sometimes it didn't, but at least it gave us a common basis of reality. I know how to preach to the choir. And I know how to identify the group that doesn't want to be bothered with the facts. But I don't know how to reconcile those things.

Based on your first column as Public Editor of the New York Times, I can see you chiseling the words 'Thou Shalt Not Commit False Equivalency' on the tablets of Margaret Sullivan's journalism commandments. Journalists can be fair to a fault, you say, especially when there aren't two equal sides to include in every story. Why has it been such a difficult lesson for the mainstream media to learn?

Because it's a safe position to go down the middle and quote everybody equally, even if there aren't equal sides. The press wants to be seen as fair, nonpartisan, not having an ax to grind, not in anybody's camp. Those are all reasonable and good impulses. But this kind of performative neutrality just doesn't work when there are basic falsehoods that a big swath of the country has accepted — for instance, that the actual elected president right now should be Donald Trump. And that's clearly not the case. There were efforts to show that the election was rigged or that there was serious voting fraud. All of that came to naught in court, in so-called audits. And yet people say they have a feeling about it. Well, feelings are not facts.

The elephant in the newsroom these days is the tight rope journalists walk, as you point out in your final media column in The Washington Post. If Donald Trump runs for president again, you say that the press shouldn't shill for his rivals in the 2024 election, but reporters should be willing to show their readers, viewers and listeners that electing him again would be dangerous. So how do you walk that tightrope without appearing to put your thumb on the scale?

You do it through reporting. You do it through facts and evidence and smart contextualization and intelligent framing. Of course, we cannot be on any side. As reporters, as fact-based journalists and as news organizations, it's not part of our role to get behind a Democrat or a Republican. That's just not what we do. But we can make very clear what the consequences are and what the reality is. That's our job. Our role is to inform the public so that the public can self-govern. And so that needs to be the guiding principle.

On a Zoom last month, University of Maryland journalism students asked you whether journalists should strive for objectivity above all else in political coverage. You said you preferred less fraught words like fairness, accuracy and truth seeking. What's the distinction?

I do believe in objectivity if you define it as it should be defined, which is we go at our subjects with an open mind and we gather evidence and we report it out. And that's what we present. That's objectivity. The analogy isn't perfect, but it's just as you would expect [objectivity] from a judge in a courtroom. You want the person to be viewing the case with an open mind. I don't believe in getting into a fight over a single word if you can describe it differently.

Liz Spayd succeeded you at The New York Times and turned out to be the last Public Editor at the Times when the position was eliminated in 2017. In her final column, Spayd asks who will be watching to see if the news media covering Trump or anything else acquit themselves well? Now, five years later, Spayd told me "if the media is to win over a distrusting public, we also need to shine a light on ourselves." So with newspapers dropping their ombudsmen or public editors and CNN canceling its Reliable Sources media criticism broadcast, shouldn't the news media be willing to open itself up to criticism if they expect government to be held to account?

"Our role is to inform the public so that the public can self-govern."

It should be. And I'm sorry to see those things go away, because I think we need the self-scrutiny. I can tell you that I was uncomfortable as the public editor of The Times, and there were many times when I'm sure they weren't very happy to have me there. Readers felt they had some place to turn and that they could make a complaint and be heard or have a court of last resort — not that I had the power to do anything. But I had the power of the pen and access to the decision makers. So I think it would be healthy and good for them to be brought back. But I don't think they will be. It seems like there was a golden age for that kind of thing and news leadership has just decided it's more trouble than it's worth. The reasoning seems to be that there's enough criticism out there without having someone on our payroll to do it.

You've prided yourself that you could always communicate with readers no matter their party affiliation. But the biggest test may have come at the 2016 Republican Convention in Cleveland. You had a front row seat to see how some of the Trump base ranted about the press. There was misogyny. You were called the venomous serpent and a lot worse. But what struck me is how brazen the attacks on the press were: the T-shirt featuring the image of a noose with the words "rope. tree. journalist. some assembly required." Did that moment begin to shake your confidence that you would continue to be able to communicate with readers no matter their party?

It certainly was a moment that shook me. It wasn't complete news to me that people didn't like the press. That goes back a long way, as Ted Koppel pointed out [at the Cleveland Convention, recalling the signs at the 1964 GOP Convention that proclaimed "Don't Trust the Liberal Media."] In Koppel's words: "It's a fifty-two-year-old meme." But the widespread acceptance that journalists are bad people and better off dead with this imagery that evokes lynching wasn't a solitary moment. It was more a representative moment because then as I talked to people, it was that sense that you are against us. So when it feels like the very public that you're trying to serve has turned away from you in a pretty hateful way, it's hard to take.

As the first woman editor-in-chief at the Buffalo News and the first woman Public Editor at the New York Times, I wasn't surprised that you suffered your share of sexism in your career. But I had to take a breath when you wrote in your book that when you proposed a reinvention of the front page of the Buffalo News, your male boss not only took credit for the idea but did so when you knew he actually hated the idea.

Yeah, that was a great moment.

So what do you tell students and young women about the sexism they may encounter as a journalist?

I would never say to young women or students — don't go into journalism, that it's horribly sexist and you're going to hate it. Of course not. It's a wonderful field. It's an important field. I think that situation has improved quite a bit. I don't think there are as many barriers for women to rise in the ranks. The Washington Post has a top editor who is a woman right now. She's a first. The New York Times has had a woman editor and has had an African-American editor. And we can encounter sexism, racism and discrimination in any job, in any field. So I don't think it's peculiar to journalism.

Since that moment in high school when your older brother David told you that your varied interests all added up to journalism, you've been on quite a journey to many sides of the craft, on bigger and bigger stages — practitioner, critic, teacher. Do you have any hills left to climb?

I'm so appreciative of having had my 40-plus-year career as a journalist. When I became the editor of The Buffalo News, I was really thrilled. It was my hometown paper. I was the first woman. And I thought this is going to be the most prominent thing I ever do, and in some ways it has been the most important thing. Certainly, one of the greatest honors. But I really wasn't anticipating the last ten years of my life when I went to The New York Times. And then coming to the Post at a very, very, contentious time in American history. So I have had the privilege of all these experiences. I love journalism. I've had a great time. But I worry about it, too, because I believe in it so much. I want it to be at its best for the purpose that it's supposed to fulfill.